There is something moving about seeing so many individual birds unite in the sky as one.

It may have something to do with our yearning for connection; with nature, with our higher selves, with each other. Whatever the reason, I hope you enjoy these videos and this story as much as I did.

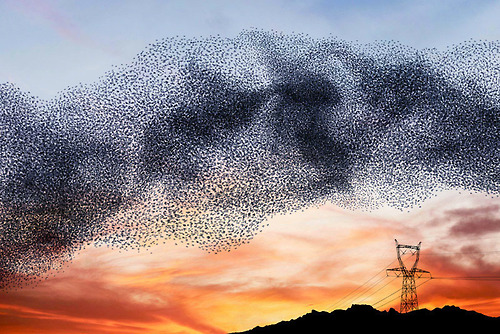

After a day out by the beach, my girlfriend and I were driving home along the coast. It was around 4 PM and we’d been casually admiring the scenery and the architecture and commenting on the various sights along our way. About twenty minutes into our journey, we saw something that we’d seen multiple times before, yet both of us were still enraptured by the view. It’s something that’s as elegant as it is strange; as natural as it is synthetic and most of all, beautiful: a flock of starlings.

The birds, too many to count, danced around the sky in what seemed like perfect unity. There were no stragglers, each bird maintained their direction and kept up with the flock which moved at an incredible pace. We stared up at the birds and both wondered “how on earth do they do that?” Their movement is so precise, so without fault yet so chaotic that it seems almost impossible that there could be so many birds all moving in such a beautifully collective manner.

Starlings Dancing in the Skies of Scotland

“Gretna Green is a Scottish village famous for the bird “air shows”. Each year European starlings migrate to wintering in Scotland. Flocks of these birds soar and form bizarre shapes in the sky as if they were dancing. Many come to witness their unusual twists in the air.”

It almost seems like science fiction, but to figure out their amazing abilities of coordination, it’s helpful to think about human interactions in similar (if less airborne) circumstances.

Crowd dynamics, the study of how crowds form and operate, sheds light on the tragedies and benefits of cramming lots of human beings together in a confined place. A recent piece in the New Yorker highlighted the case of a Walmart worker, Jdimytai Damour, who was crushed to death as thousands of people clamored for bargains on Black Friday; an American tradition where stores mark heavy discounts on their products.

In this case, Damour was trampled as people entered the store not because they were feeling particularly brutal or frenzied, but because the people at the back of “the crush” couldn’t see what was happened at the front. They simply kept moving forward, unaware that they were pushing the people in front of them and, in this case, trampling the poor employee. Similarly, the people in the middle who are getting pushed from behind keep moving forward as well.

There are countless other examples of this but it highlights the basic problem that humans aren’t very spatially aware, especially in large crowds of people. The crowd almost becomes its own entity, made of up individual movements.

So how do starlings, in larger crowds and while flying, not violently collide in a similar way? How do they not get left behind or lost? How do starlings manage to “dance” when nobody’s telling them what to do?

In 1985, Craig Reynolds, a computer researcher, designed a program that emulated a flock’s flight pattern using three “steering behaviors” – rules the birds (or “boids” as the program was called) must follow in order for the flock to work. Firstly, there’s “separation”, where the boid avoids crowding nearby flockmates. Second, there’s “alignment”, where the boid steers towards the average heading of local flockmates. Finally, there’s “cohesion”, where the boid moves towards the average position of its local flockmates.

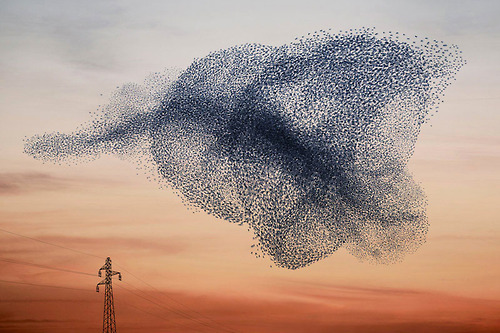

A Bird Ballet

“Filmmaker Neels Castillon was on a commercial shoot a few days ago, waiting to catch a helicopter flying into a sunset, when suddenly tens of thousands of starlings unexpectedly swarmed the sky in an enormous dance known as a murmuration. With his director of photography, Mathias Touzeris, the two filmed for several minutes capturing magnificent footage. How do thousands of birds simultaneously make such dramatic changes in their flight patterns? After tons of research, scientists still aren’t sure.”

These three rules explain why starlings remain so unified, even when performing complex swirls and dives. However, it wasn’t until fairly recently that we actually saw this in action. In 2008, scientists in Italy took on the time-consuming job of studying the flocks and blamed our ignorance of a flock’s movement simply on a lack of data. To combat this, the team used inter-linked cameras to measure how a flock works and took data from around 500 “flocking events”. Only 50 of these worked out well enough to be used (highlighting the painstaking nature of the work).

They effectively established data that found what Reynolds had designed in 1985: for the flock to work, each bird must follow three rules:

Avoid collisions (separation)

Move-in the same direction as your neighbors (alignment)

Remain close to them (cohesion)

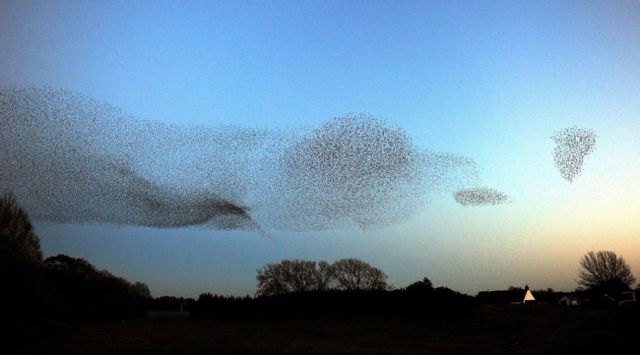

The researchers described the work as “the first large-scale study of collective animal behavior” and it cements the basic rules for collective animal movement. Each unit simply stays aware of these three rules and using their fast reflexes the starlings’ autonomy makes them united.

The question of why they do this isn’t certain, but it’s likely as a defense against predators, a way to keep warm and exchange messages. A group of 1,000 starlings looks a lot less appetizing than a single bird and the flock even creates “high-density borders”, what the researchers describe as a “wall effect”, to confuse potential predators. They even take it in turns to be on the outside.

The starling’s flock is the ultimate example of the “collective”, where the actions of the individual shape the group. The internet, with its groups and wikis, often mirrors the starling’s flock and writers such as Kevin Kelly have spoken about the ‘hive mind’ as a positive entity where “nobody is smarter than everybody”.

A bird ballet from Neels CASTILLON on Vimeo.

In his book, Out of Control, Kelly describes a 1991 lecture by Pixar co-founder Loren Carpenter. In the conference hall, cameras tracked the audience of around 5,000 people, dividing them into two groups: left and right. Then, when the audience grasped the basics of a simple Pong game they were given the task of flying a simulated airplane.

Loren Carpenter launches an airplane flight simulator on the screen. His instructions are terse: “You guys on the left are controlling roll; you on the right, pitch. If you point the plane at anything interesting, I’ll fire a rocket at it.” The plane is airborne. The pilot is…5,000 novices. For once the auditorium is completely silent. Everyone studies the navigation instruments as the scene outside the windshield sinks in. The plane is headed for a landing in a pink valley among pink hills. The runway looks very tiny.

Islands and Rivers

Kelly describes it as “both delicious and ludicrous” that the passengers of a plane are collectively flying it and that “as a passenger, you get to vote for everything.” But as the plane came into land things started to go wrong. The plane began to swing down, wing-first into the runway, looking like the crowd -the hive- had failed to keep it in the air.

Then, without a single order, without any communication or leader, they made the plane dart upwards and began a new approach. Even when doom looked imminent, the crowd, somehow, managed to save the 5,000 passengers from their self-imposed death.

Like starlings, they made the impossible-looking collective dance of a flock work. This “flockness” occurs even when the creatures, be them human or starling, aren’t aware of their collective shape or alignment. The individual forms the group.

Sources:Karmajello,thatscurious,izismile