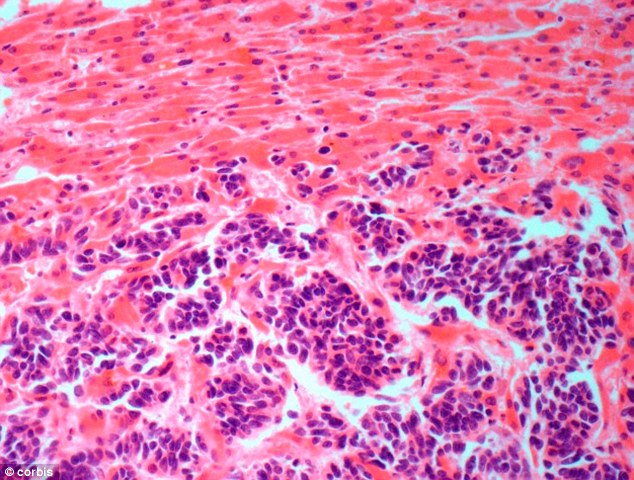

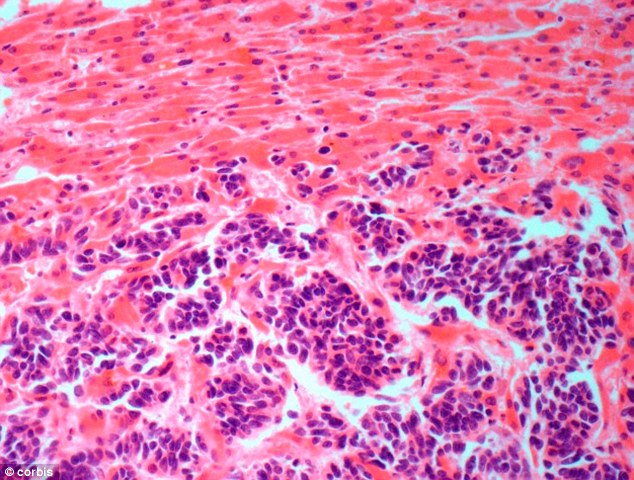

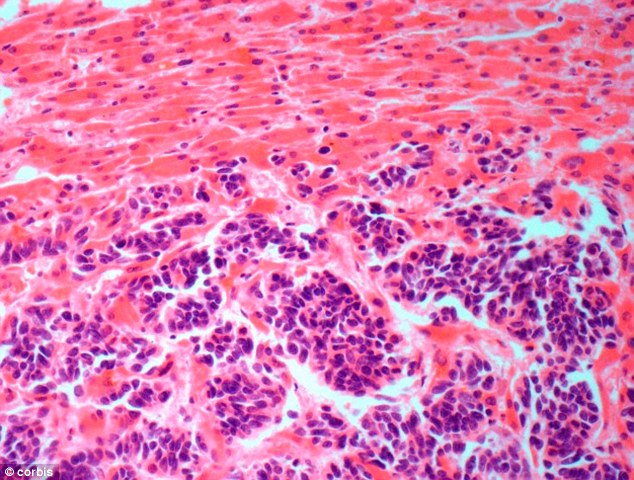

A study by British universities have discovered for the first time how cancer cells migrate from organ to organ. Findings could transform the way cancer is treated, helping experts block the movement of the disease. Most cancer deaths are caused by secondary tumours in vital organs such as the brain or liver, which spread from the initial source. Team discovered cancer cells change into a ‘liquid’ state to move through the narrow passages of the body.

A breakthrough in cell research may pave the way for treatments which stop cancer spreading through the body. Scientists at British universities have worked out for the first time how cells are able to migrate from organ to organ. The new research, spearheaded by biologists at University College London, could transform the way cancer is treated. Crucially, the discovery has enabled scientists to work out how to block the movement of cells.

It means that aggressive cancer, which can quickly advance away from a primary tumour, might in the future be effectively frozen and isolated as soon as it is detected. Most cancer deaths are not caused by initial tumours, but by secondary tumours in vital organs such as the lungs or brain that are created by cancerous cells invading other places in the body. If the research can be used to develop an effective treatment it could save millions of lives each year. Professor Roberto Mayor, whose paper was published today in the Journal of Cell Biology, said: ‘This is an important breakthrough in the understanding of how cells move, which we strongly believe provides an insight into the way cancer spreads.

‘There is a long way to go from here to a cancer treatment, but it provides a theory as to how a tumour may be isolated and the cells stopped from moving and spreading.’ Professor Mayor’s team, along with researchers at Kings College London, Cambridge University and Akika City University in Japan, discovered that cells have to change state in order to move along the narrow passages in the body. The links between each cell is weakened, transforming them into a liquid-like state and allowing them to invade other parts of the body.

Vitally, the scientists also discovered the chemical signal which prompts the change. By switching off the signal, they were able to solidify the cells, effectively blocking any further movement. The research has so far only been shown to work in non-cancerous embryonic cells, but Professor Mayor is confident that it could be replicated for the way cells spread from a tumour and invade other parts of the body.He said: ‘It is likely that a similar mechanism operates during cancer invasion. ‘Many of the cellular processes that we now know happen in cancer were first discovered in these same embryonic cells.’ His researchers found that a molecule called lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) was responsible for weakening the bonds between cells, allowing them to change from a solid-like to a liquid-like state and allowing them to flow between tissues in the body.

Vitally, the scientists also discovered the chemical signal which prompts the change. By switching off the signal, they were able to solidify the cells, effectively blocking any further movement. The research has so far only been shown to work in non-cancerous embryonic cells, but Professor Mayor is confident that it could be replicated for the way cells spread from a tumour and invade other parts of the body.He said: ‘It is likely that a similar mechanism operates during cancer invasion. ‘Many of the cellular processes that we now know happen in cancer were first discovered in these same embryonic cells.’ His researchers found that a molecule called lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) was responsible for weakening the bonds between cells, allowing them to change from a solid-like to a liquid-like state and allowing them to flow between tissues in the body.

Blocking the LPA molecules – which could be achieved through a simple injection – stopped the cells’ movement. Professor Mayor said: ‘This suggests a promising alternative in which cancer treatments might work in the future, if therapies can be targeted to limit the tissue fluidity of tumours.‘ Our findings are important for the fields of cell, developmental and cancer biology. Previously, we thought cells only moved around the body either individually or as groups of well-connected cells. What we have discovered is a hybrid state where cells loosen their links to neighbouring cells but still move en masse together, like a liquid. Moreover, we can stop this movement. He added: ‘I emphasise that we are far off a treatment – but it might be that you could inject an inhibitor around a tumour, blocking the LPA. The tumour will become solid and will not move. It means you stop it spreading.’

By Ben Spencer via Dailymail