I was a police officer for 20 years, enforcing drug laws in California and thinking I was doing my part for society. But what made me think properly about drug use for the first time was my experience with my older brother, Billy. I had watched him struggle with a lifelong problem with drugs. But I still did not understand what it meant to be Billy until my husband convinced me to open up my heart and our home to save him in 2002.

It was in this intimacy of watching Billy try, during the year he lived with us, to live up to the expectations of society and those he loved that I realized that our society’s portrayal of people with chronic drug problems was both damaging and morally flawed.

By society’s standard, my brother was a criminal. His struggles with addiction taught me many things. He had many years of sobriety, interspersed with the setbacks that addiction specialists know so often come with the condition. But because of an emphasis by the court system on abstinence-only drug programs, and an emphasis on punishment over progress, these normal and accepted setbacks in recovery were exacerbated by harsh penalties. Because of Billy’s felony convictions for drugs, he was unemployable. He lacked healthcare until we stepped in. Without us, my brother would have been on the streets. Yet despite our help, my brother passed away from an accidental overdose of psychotropic medications and alcohol.

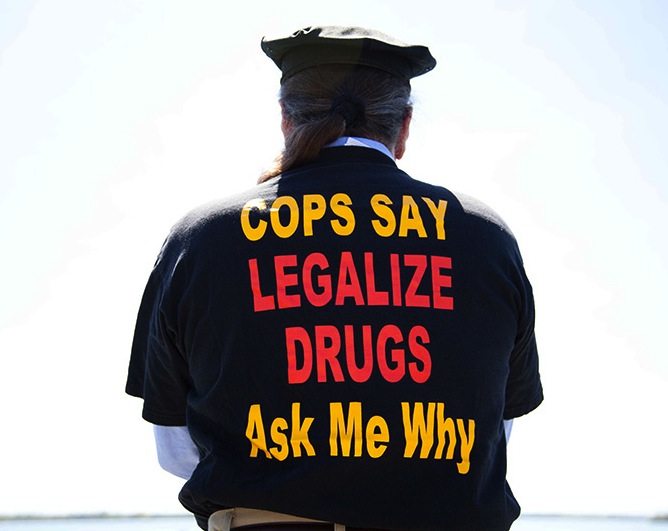

After having my eyes opened to the realities of drug use, I realized we could not arrest our way out of this problem. I joined Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP), a group of law enforcement officials opposed to the war on drugs. Some people are surprised to find that police, prosecutors, judges and others arguing for legalizing drugs, but in many ways we are the best positioned to see the injustices and ineffectiveness of the criminal justice system up close.

Decriminalization laws can do many good things. They reduce law enforcement and incarceration costs, allow police to focus on more pressing matters and keep casual users out of a criminal justice system that already destroys far too many lives. However, LEAP supports full drug legalization because of what decriminalization doesn’t do.

We’ve seen how federal grants and civil asset forfeiture laws (whereby police can take your property and use or sell it for their own benefit, even if you’re never charged with a crime) encourage police to go after drug offenders while real criminals roam free. We’ve seen people die of overdose. We’ve seen people go to prison who had no business being there. And we’ve seen that none of this has reduced drug use or addiction. In spite of more than 40 years of the war on drugs—and the trillion dollars we’ve spent—Americans now have access to drugs that are cheaper, more potent and just as readily available as when the drug war started. Who exactly is prohibition supposed to be helping?

But that doesn’t mean that everything we’ve tried has failed. As we work towards a world in which drugs are legalized and regulated, we can take smaller steps toward smarter drug policies by supporting decriminalization laws and by implementing harm reduction strategies, which address drug problems using a public health model that reduces death, disease and addiction.

In America we practice a different form of decriminalization than, for example, in Portugal, where you can possess up to 10 days’ worth of any drug with only an administrative or civil penalty. Decriminalization laws vary by state but generally mean that first-time offenders will not go to prison or be burdened with a criminal record for possession of a small amount of drugs for personal consumption. But even in states that have liberalized their drug statutes, there are still many collateral consequences for something as simple as a drug conviction—including the potential loss of federal aid for student loans, denial of social welfare benefits such as housing and food stamps, denial of voting privileges or professional licenses, and termination of parental rights.

Decriminalization laws can do many good things. They reduce law enforcement and incarceration costs, allow police to focus on more pressing matters and keep casual users out of a criminal justice system that already destroys far too many lives.

However, LEAP supports full drug legalization because of what decriminalization doesn’t do. It doesn’t set up a system of regulated purity, so users don’t know what they’re putting in their bodies or how strong it is, increasing the risk of overdose. And if someone does overdose, their friends may be afraid to call for help for fear of being prosecuted. Decriminalization doesn’t enact age restrictions on sales or stop the violence generated by upheavals and turf wars caused by law enforcement intervention. It doesn’t necessarily prevent large racial disparities because of the wide discretion in charging by prosecutors. And it does nothing to impact the enormous profits being made from drugs by violent criminal gangs, or to stop the violence generated by upheavals and turf wars caused by law enforcement intervention.

People working in public health understand that harm reduction strategies produce positive health outcomes. Even law enforcement is beginning to understand the necessity of thinking outside the “drug war” box to save lives by implementing and supporting programs that use the precepts of reducing harms to those using drugs. By supporting “Good Samaritan” laws that allow witnesses to an overdose to save a life by calling 911 without threat of criminal prosecution, criminal justice professionals are recognizing that the threat of criminal sanctions has contributed to too many deaths.

Seattle, which gives officers the ability to connect low-level, non-violent drug dealers and users with treatment and services as an alternative to jail, is an example of a law enforcement agency using harm reduction strategies to improve the lives of those struggling with addiction. The Quincy, Massachusetts Police Department is another. By mandating that its officers carry naloxone, a cheap and effective drug that can reverse opioid overdoses, they saved more than two hundred lives in just over three years. Imagine how much difference it would make if police departments across the country adopted a similar model.

It is clear to me that implementing decriminalization and harm reduction models are vital steps on the way to a smarter drug policy and should be supported. But to stop there is short-sighted, as it will leave unresolved the violence associated with the illicit market, as well as the other inevitable consequences of an ineffective drug policy based on politics, rather than what we know works.

Isn’t it time that we demand that our government use science, best practices and compassion to design drug policy?

Written by Diane Goldstein of www.substance.com

About the Author:

Lieutenant Commander Diane Goldstein (Ret.) is a board member of Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, a group of law enforcement officials opposed to the war on drugs.

Source:Substance